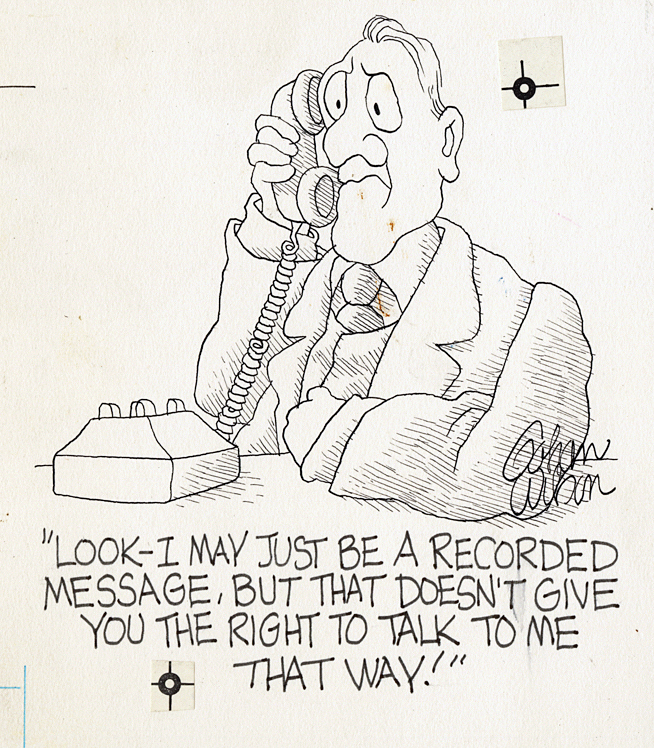

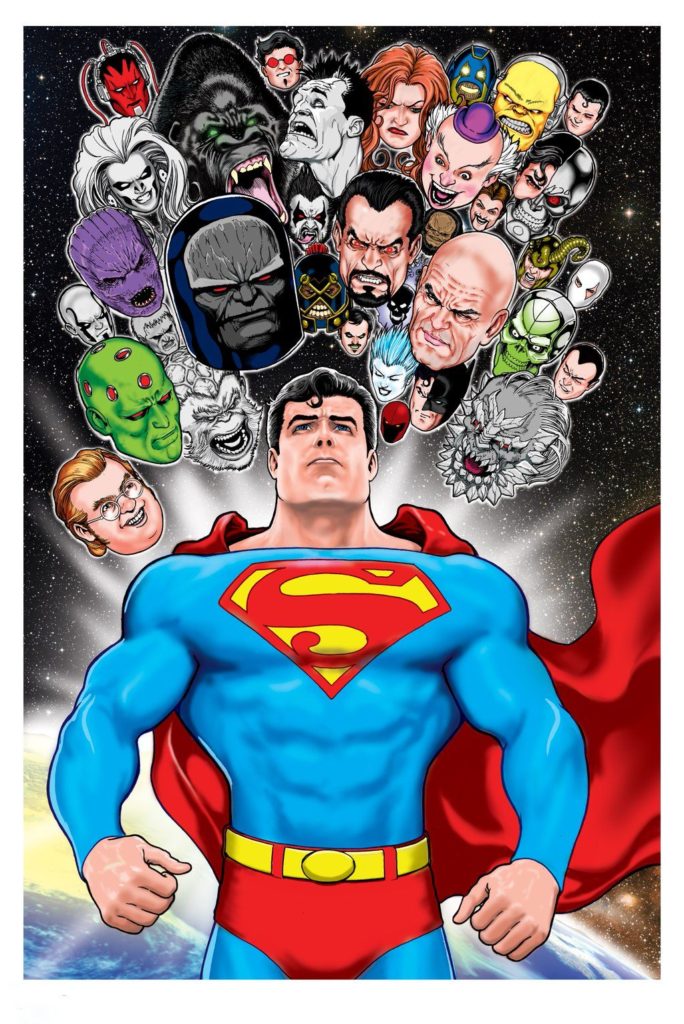

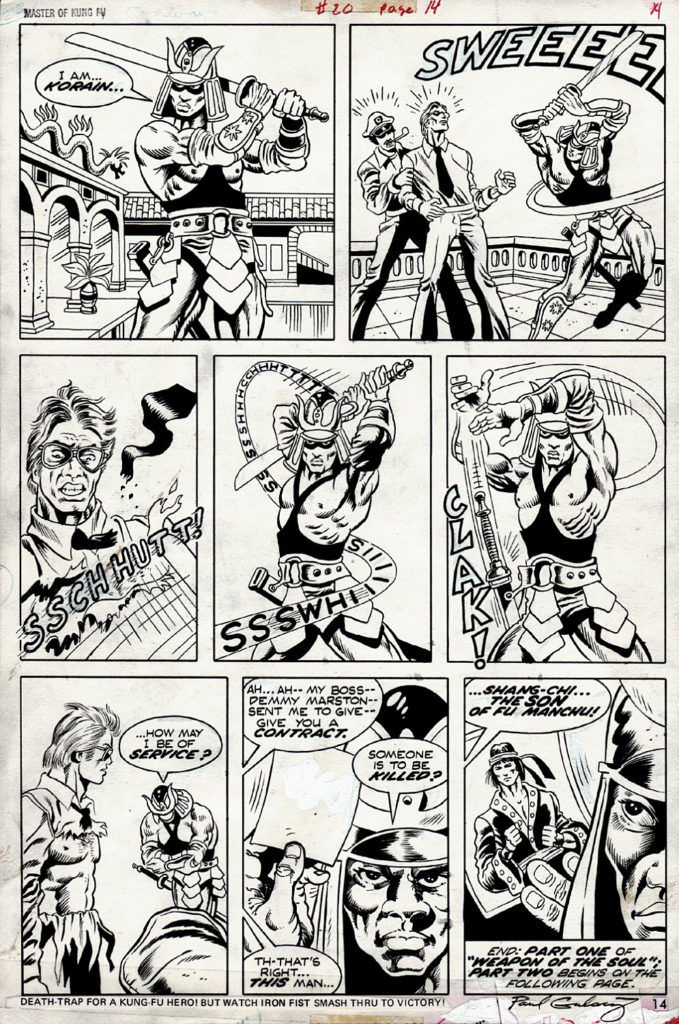

Gahan Wilson — Hang Up

Published Cartoon, Unknown Magazine, 70s – 80s

The National Cartoonists Society would be poised for their annual awards event this month if it wasn’t for the COVID pandemic, so it’s a good week to celebrate cartoons. Plus, we need some laughs.

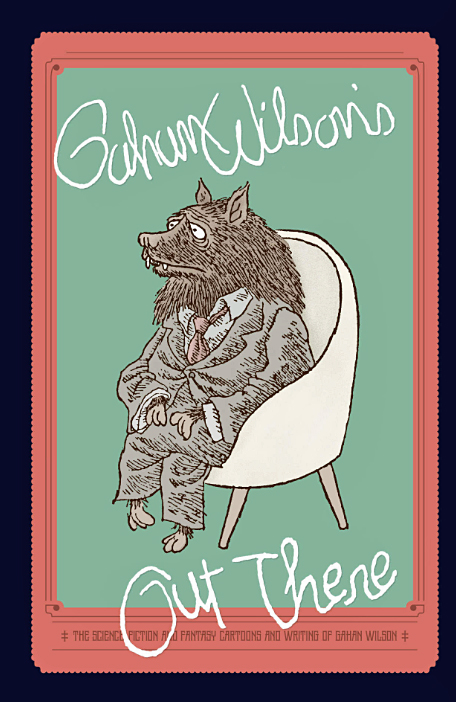

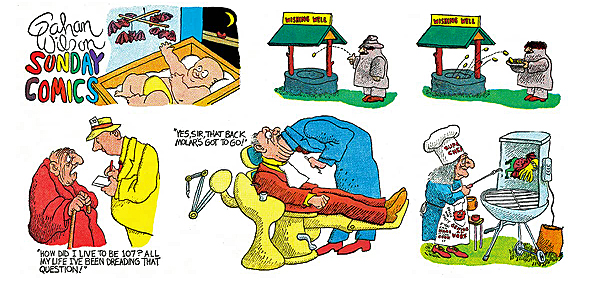

Gahan Wilson was one of the great cartoonists of the 20th century, period.

Don’t trust me. Here’s what the New Yorker said in his obit. They know something about cartoons and cartoonists:

“Wilson excelled at depicting the extraordinary. Although he habitually delved into that dark funny corner that we associate with Charles Addams, his style was singular. He liked to depict ordinary folks encountering some kind of anxious terror, or experiencing the unthinkable in mundane places. It’s a man at a pizza counter hovering over an entire pizza—the man’s mouth the same oval shape, the same size, as the whole pie. It’s fishermen on a calm lake, with one about to be murdered by the other, who is removing a human mask to reveal his true monster self. Wilson’s art is both the heart-thumping you feel when you dare look under the bed and the relieved inner laugh you let loose after he’s scared the pants off of you.“

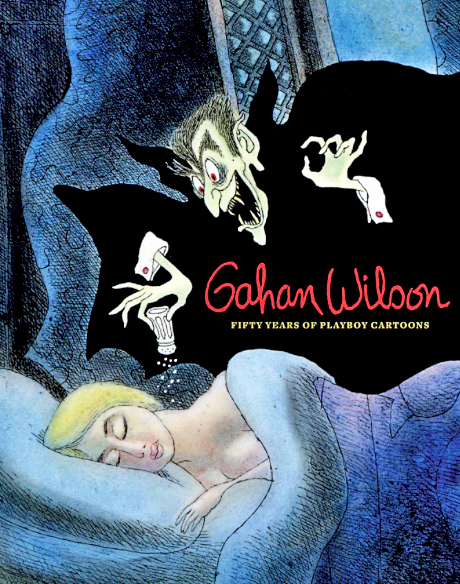

Or, let’s see what Hugh Hefner said about Wilson’s cartoons in Playboy:

“Gahan Wilson was an immediate hit with our readers and a perfect contrast to our usual, more sexual cartoon fare,” Mr. Hefner wrote in the introduction to “Gahan Wilson: 50 Years of Playboy Cartoons” (2011).

“By the early 1960s,” he continued, “I could say with real satisfaction that no other magazine in the world — The New Yorker included — had a cartoon stable the equal of Playboy’s. And no cartoonist was more popular, or more enduring, than Gahan Wilson.”

Wilson was one of my favorite cartoonists as a kid, and still is. If there’s a missing link between Charles Adams and Gary Larson, you’ve found him here.