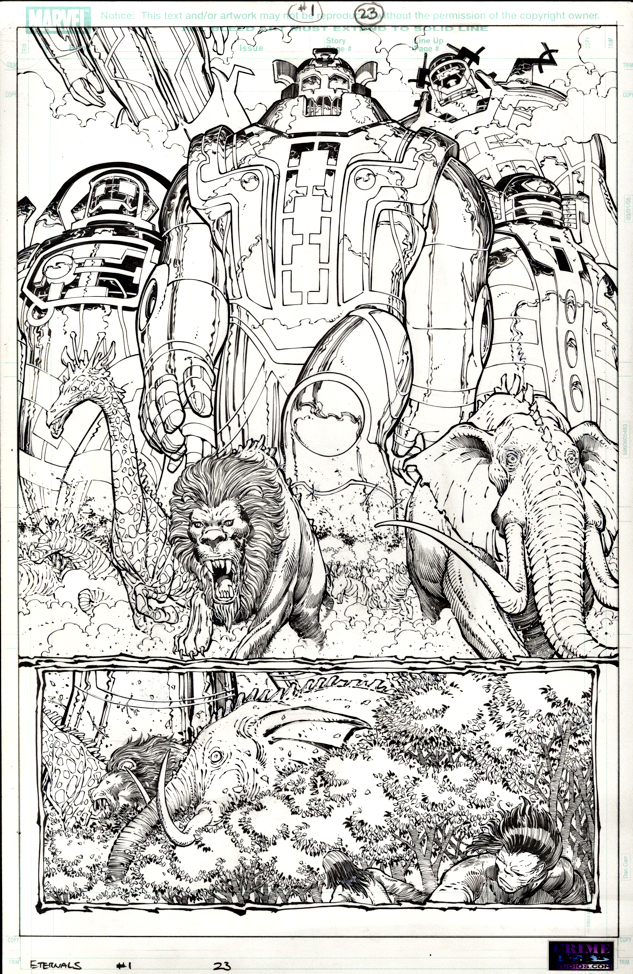

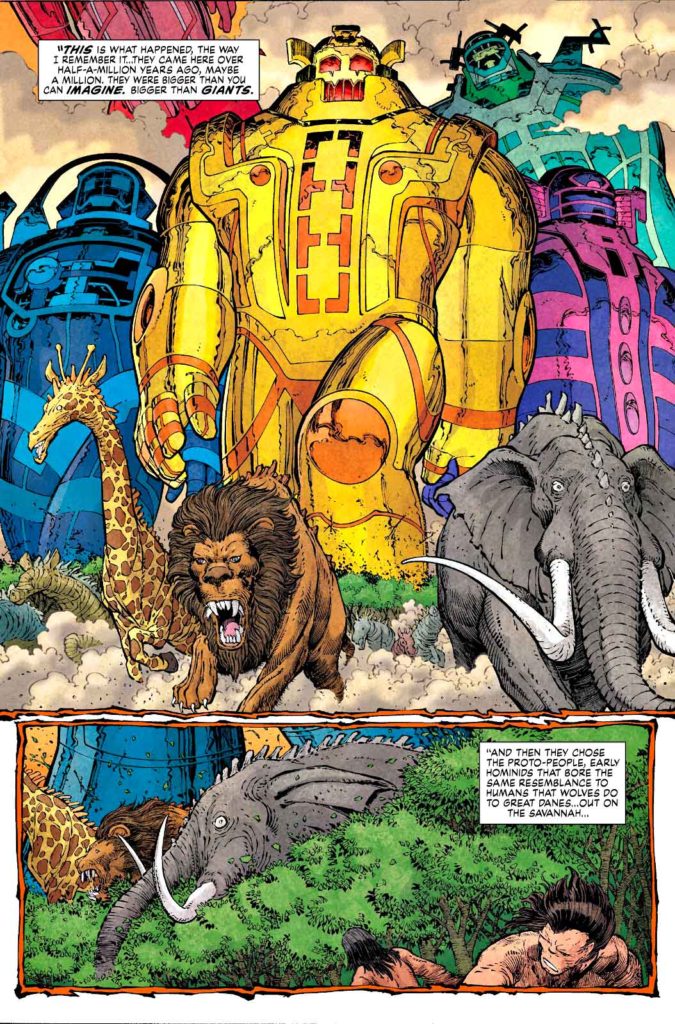

John Romita Jr. — The Coming Of The Celestials

Eternals #1, August 2006

Jack Kirby’s Celestials walk the earth, courtesy of Neil Gaiman and John Romita’s 2007 mini-series, as detailed previously here.

And finally, after a year or so of pandemic-related delays, they (presumably) walk on the big screen this Friday.

Early buzz on the film is quite good, but if I’m guessing, regardless of story and cast performance, Kirby fans will judge the film on whether the cinematic realization of the Celestials matches — or even amplifies — Jack’s giant vision.

In a few days, we will all see for ourselves