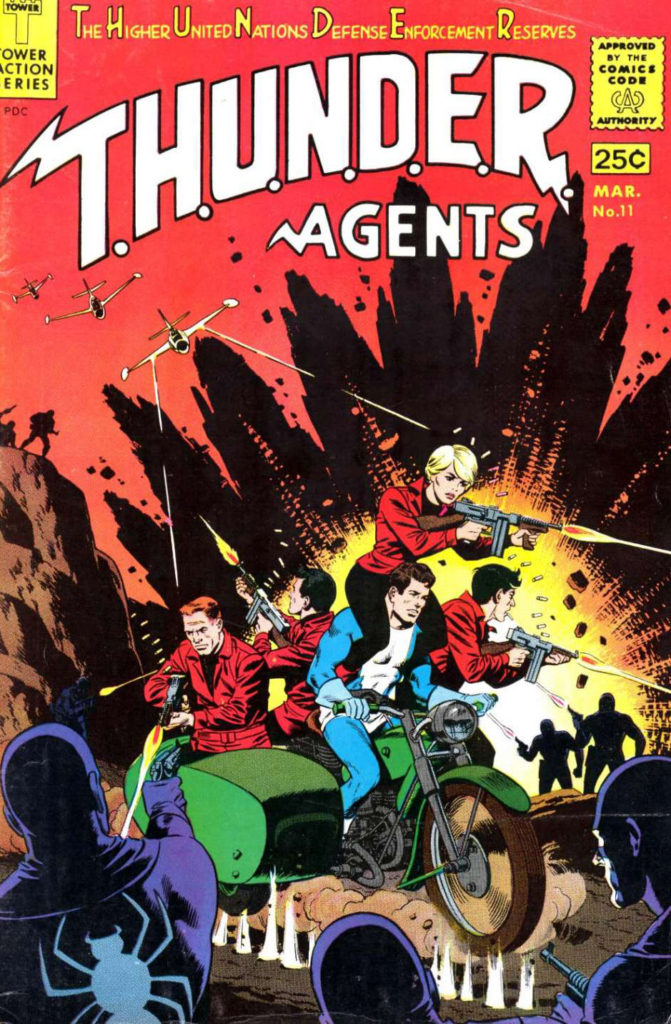

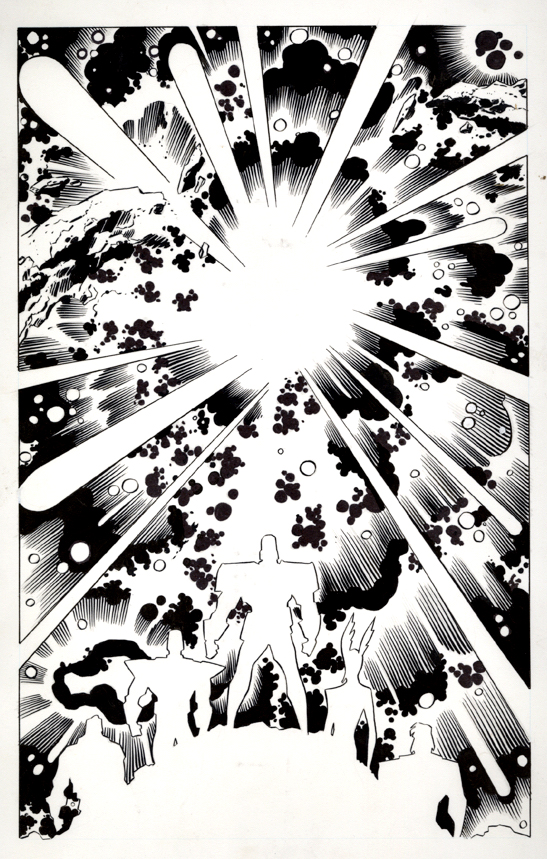

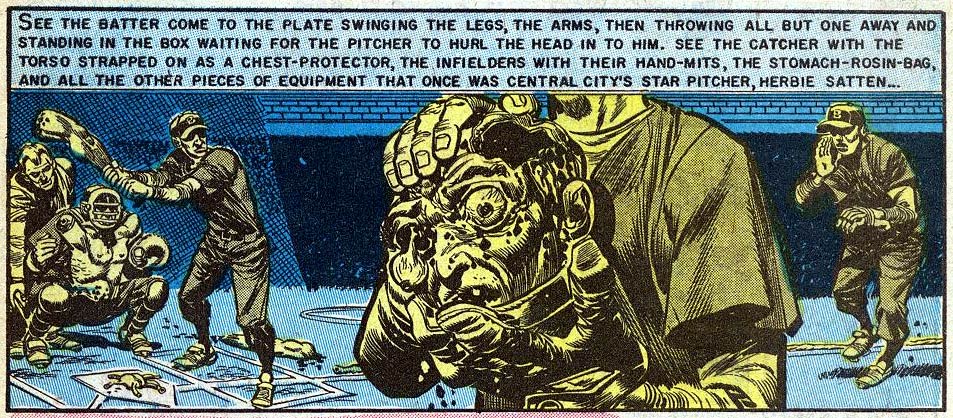

Wallace Wood — Agent of Change

T.H.U.N.D.E.R. Agents #11, March 1967

Wallace Wood made his move.

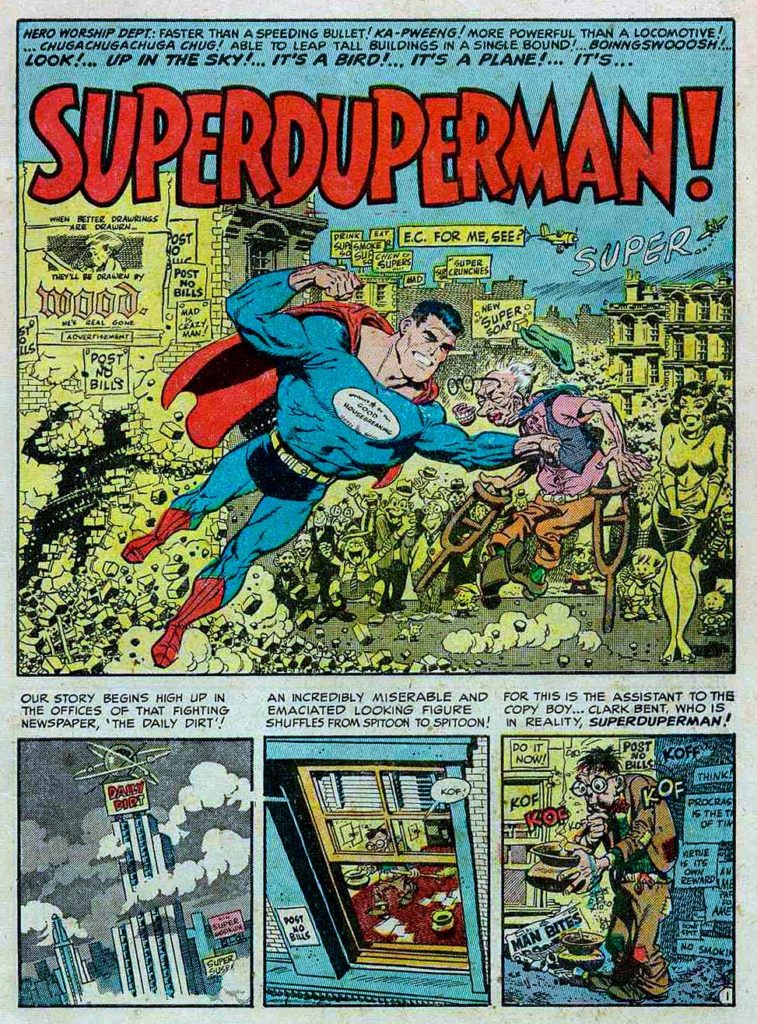

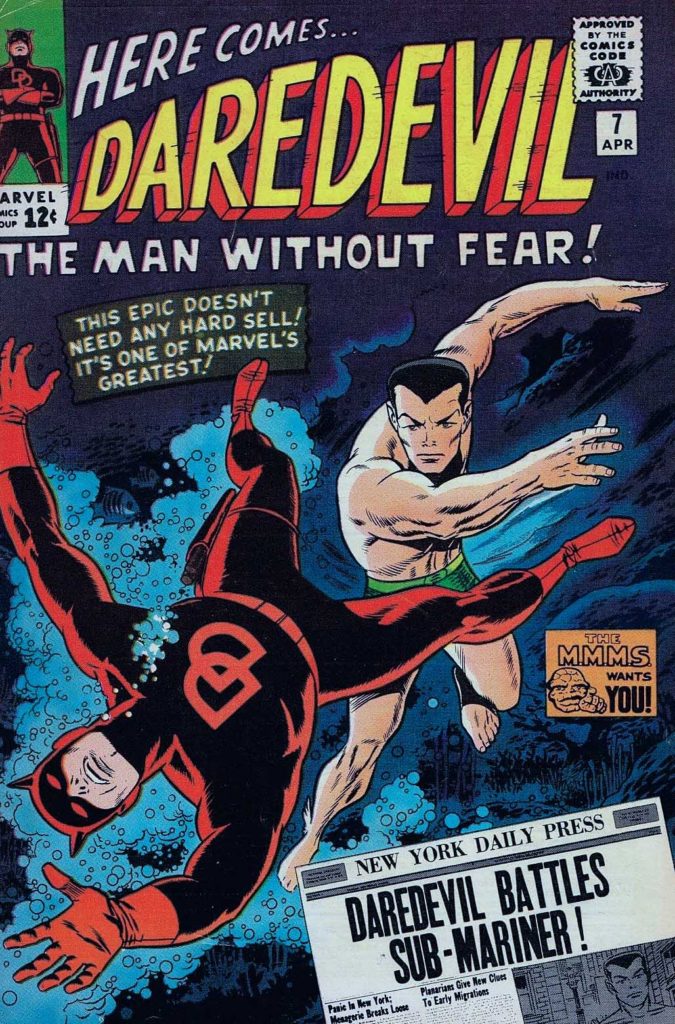

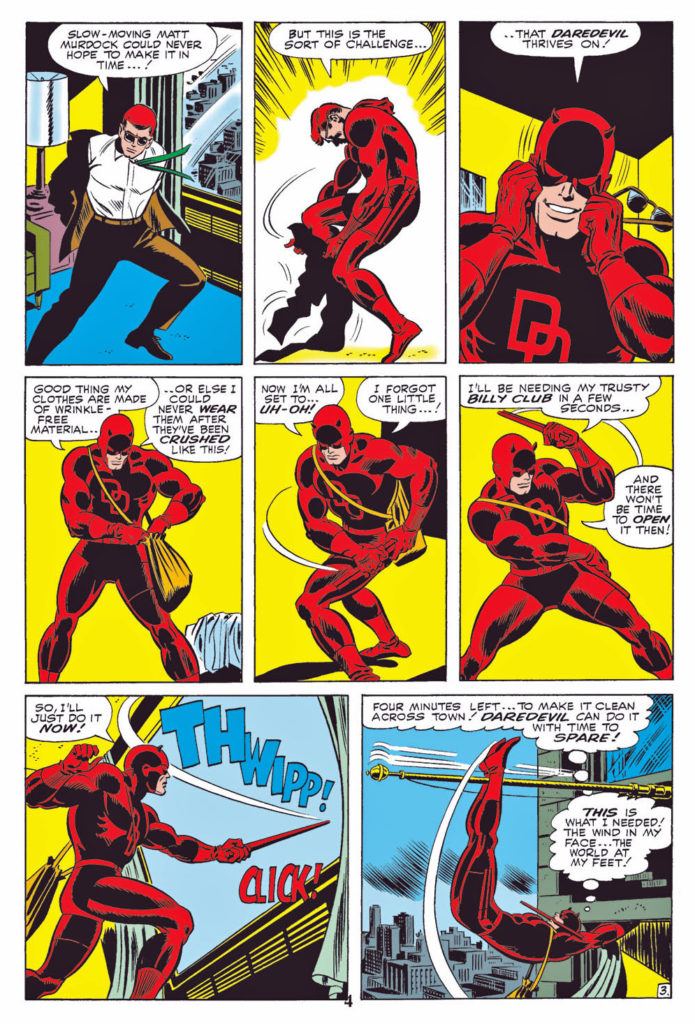

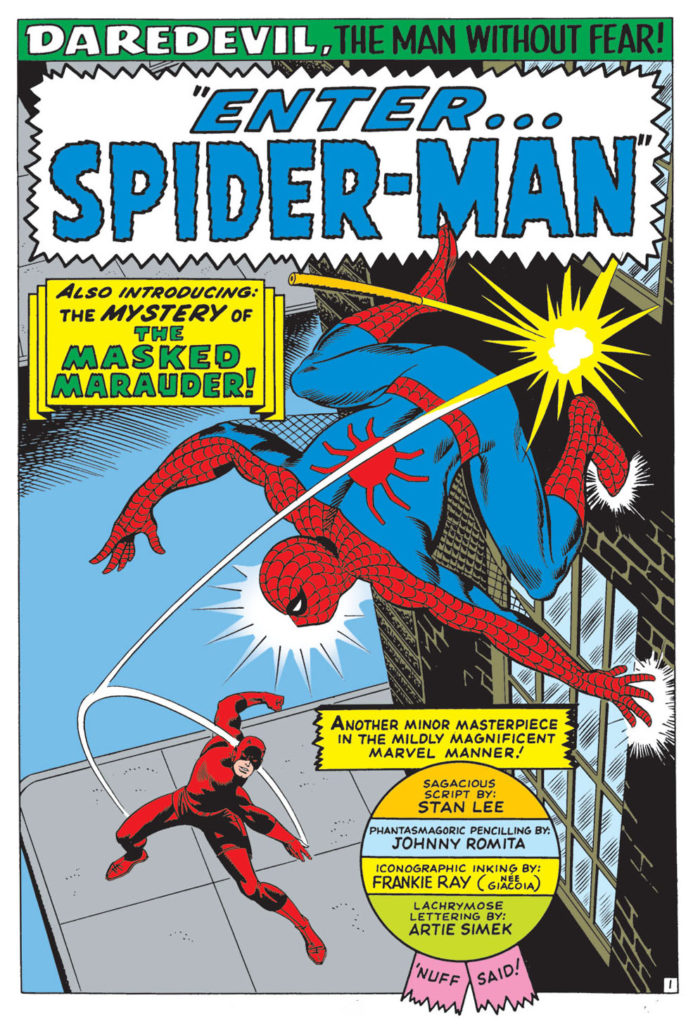

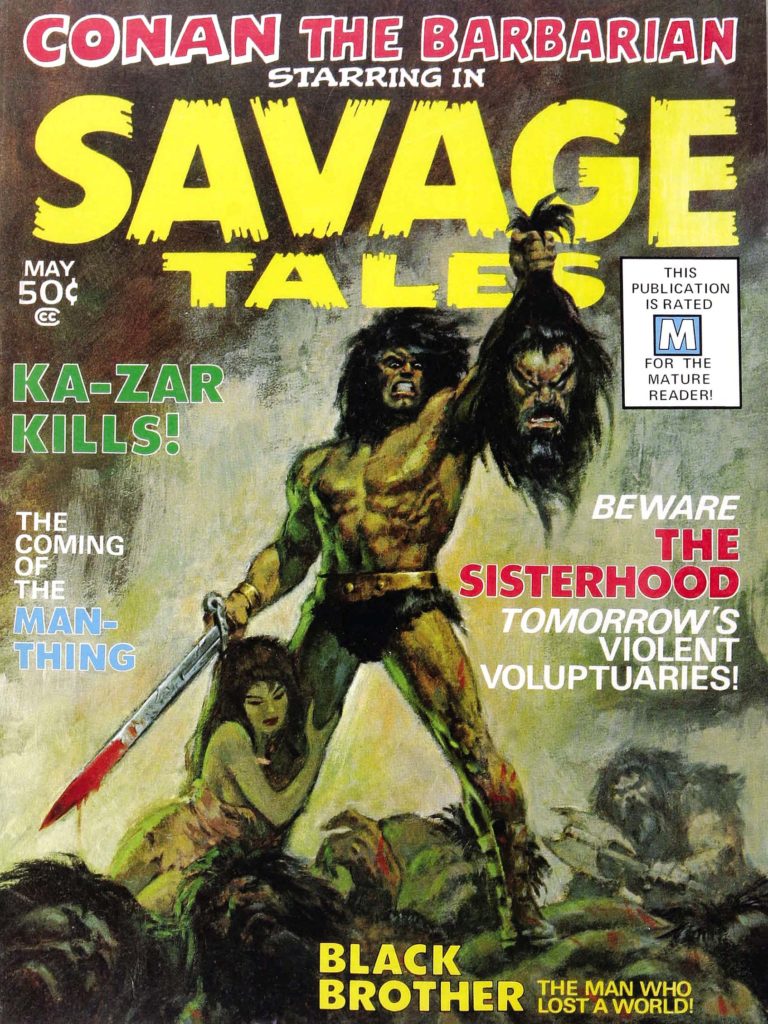

The frustrated artist, working “Marvel style” on Daredevil — plotting AND drawing — but only paid for the art, heard about a new opportunity. Tower, primarily a book publisher, had decided to take a leap of faith into the comics biz, and Woody was ready to help them.

It was the perfect role for Woody, who had carte blanche to develop the comics as hew saw fit. He was artist, storyteller, art director and defacto editor — all rolled into one.

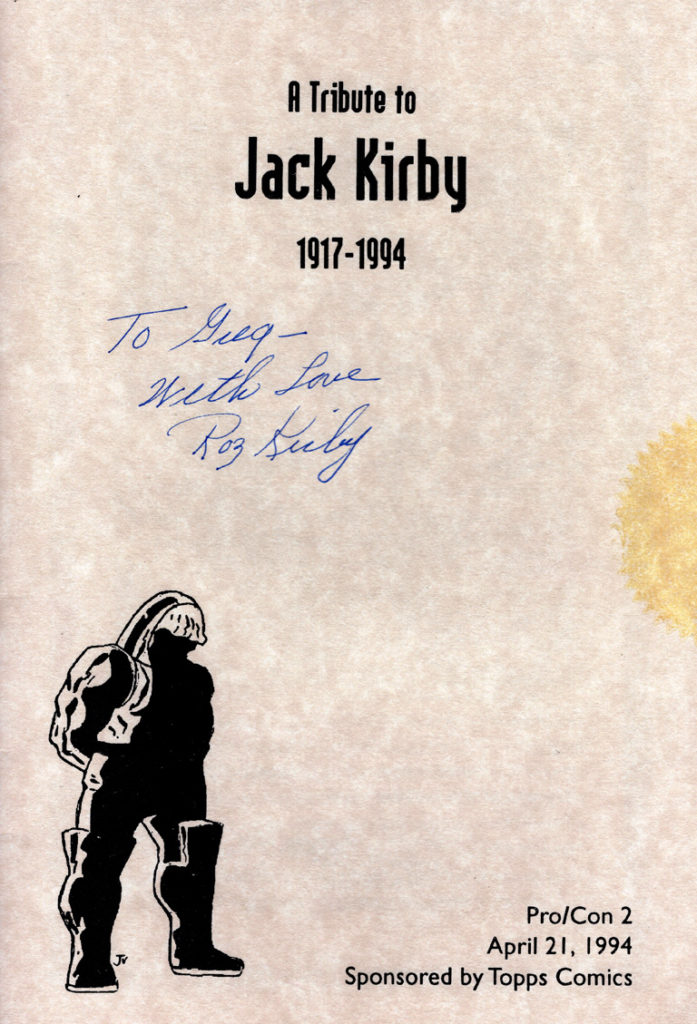

And with the help of friends/colleagues Len Brown (Topps Mars Attacks) and Dan Adkins, T.H.U.N.D.E.R. Agents was born.

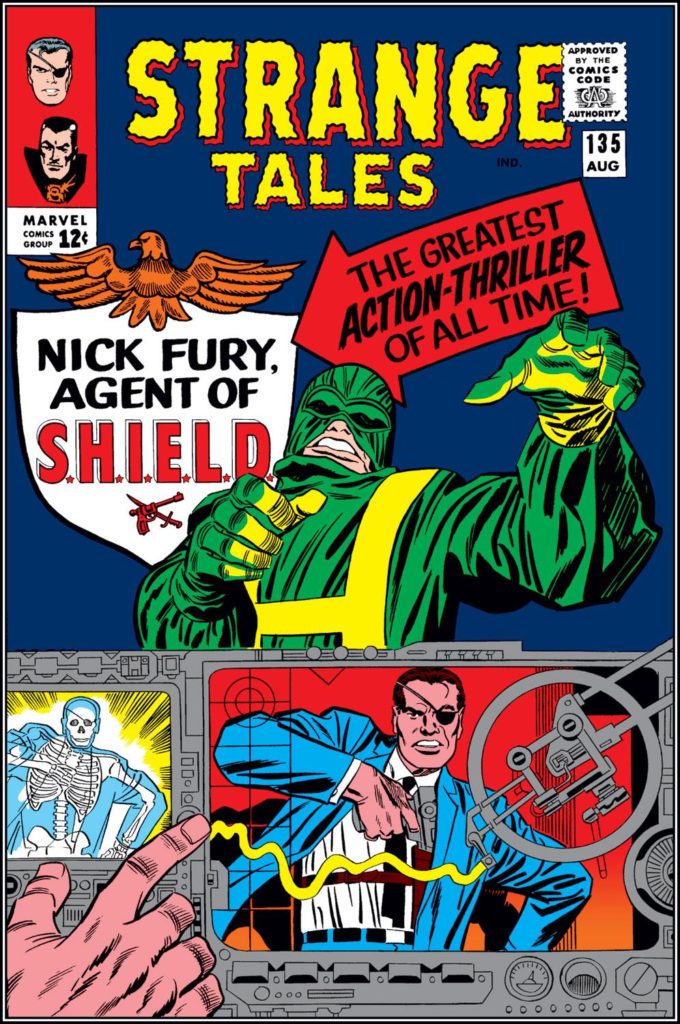

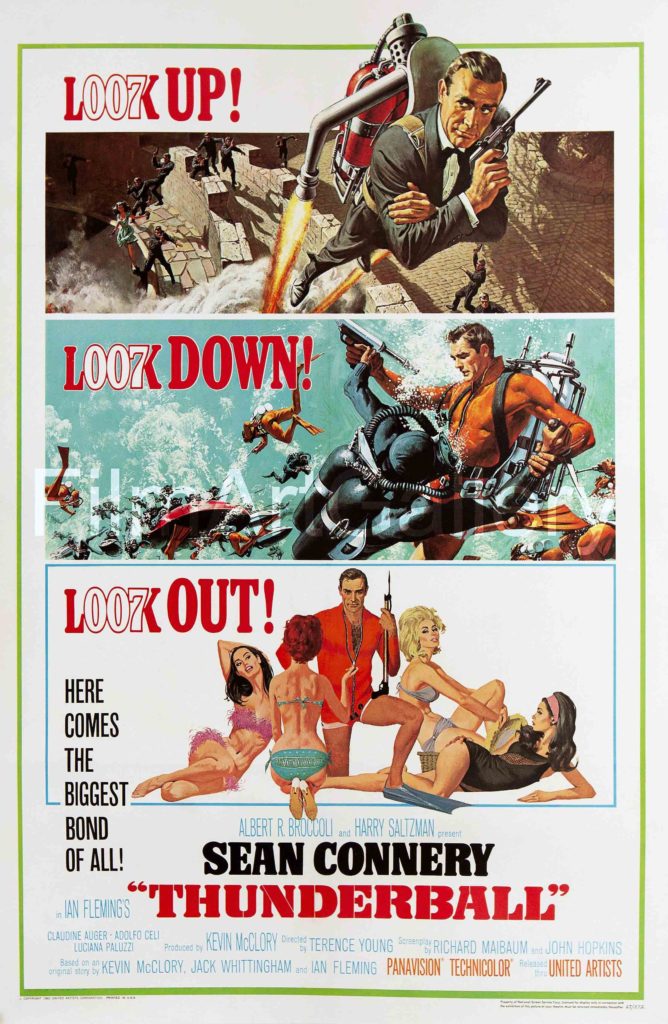

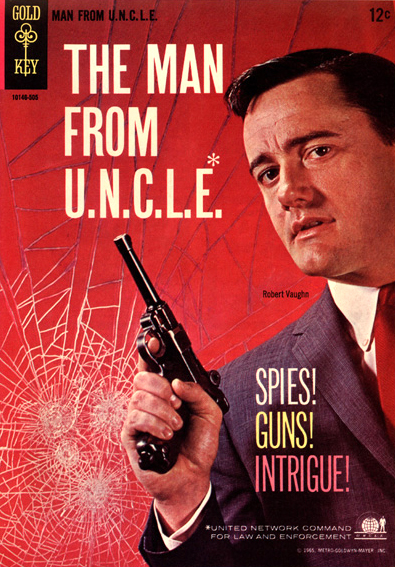

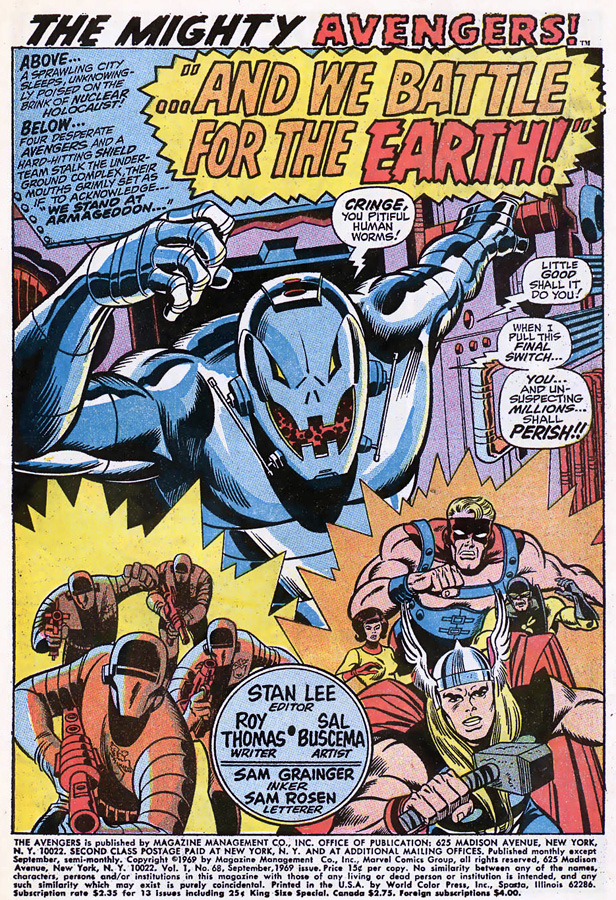

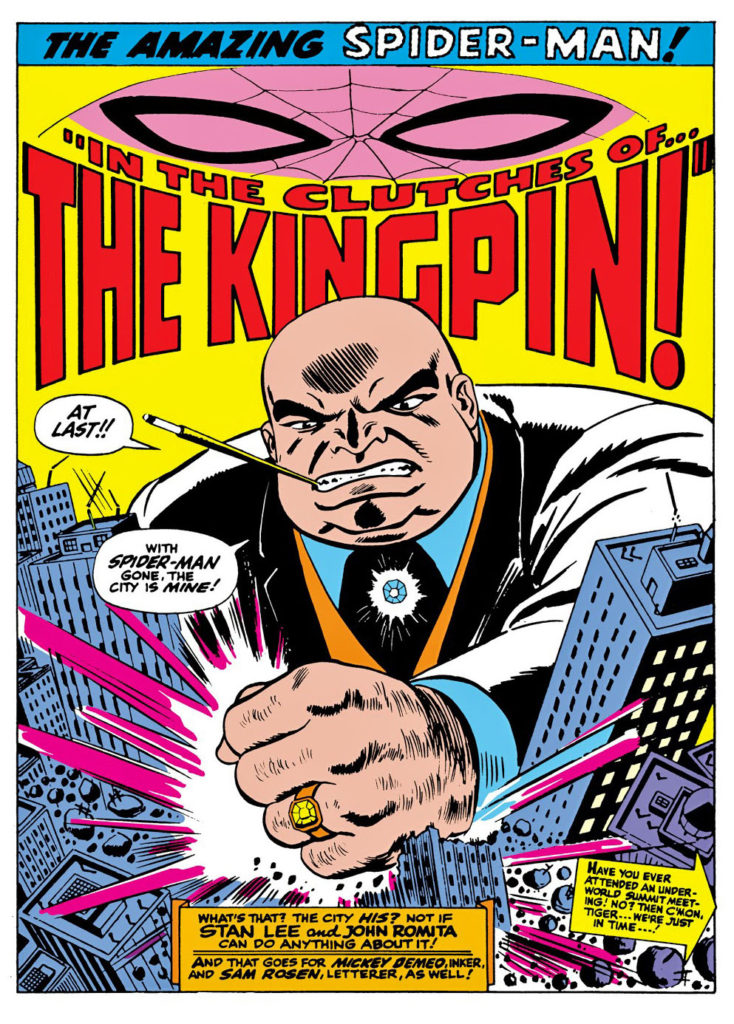

Combining a super powered team (think Justice League) with a secret spy organization (ala S.H.I.E.L.D., which had just launched a few months prior) T.H.U.N.D.E.R. Agents was an effort to capitalize on the secret agent pop culture craze. (James Bond, Man from U.N.C.LE., et al.).

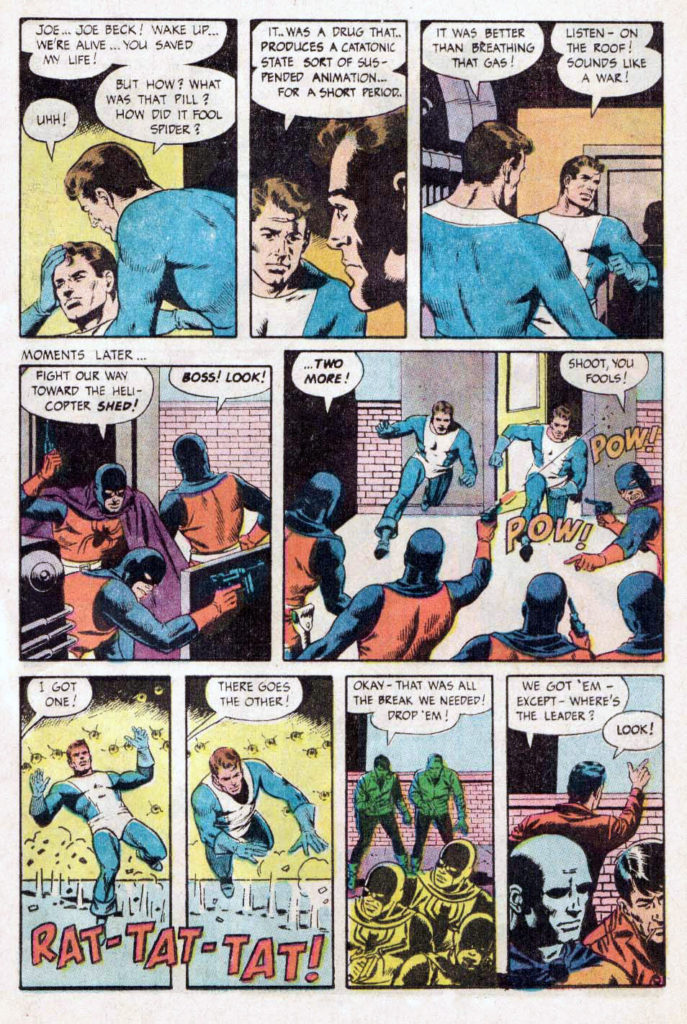

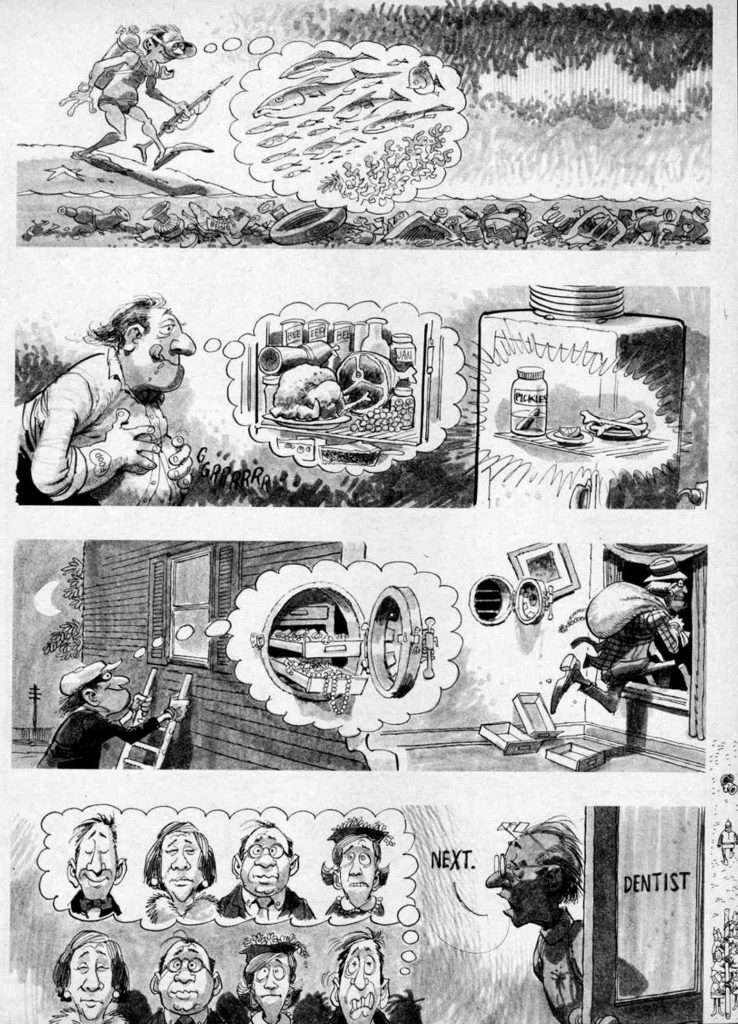

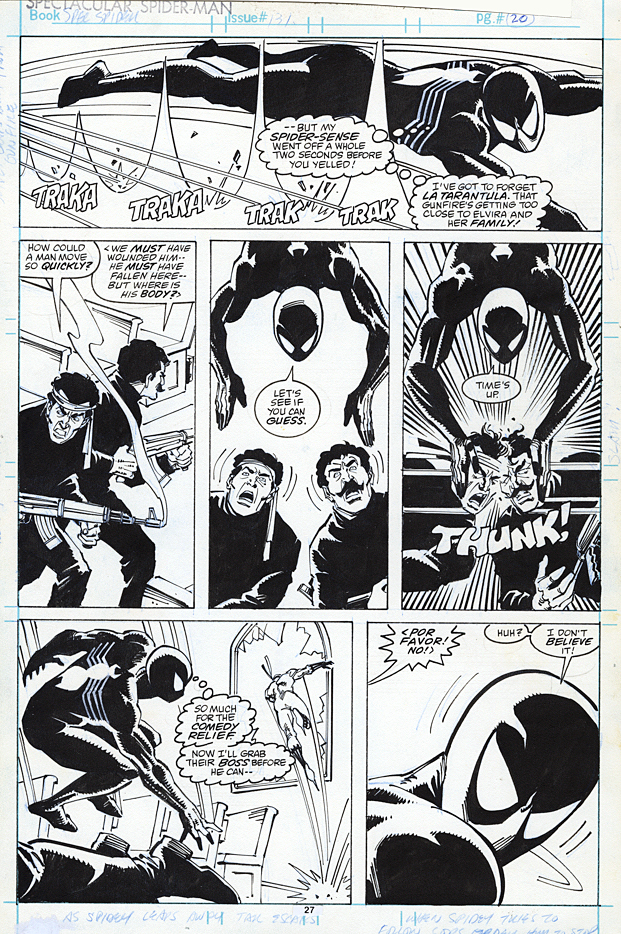

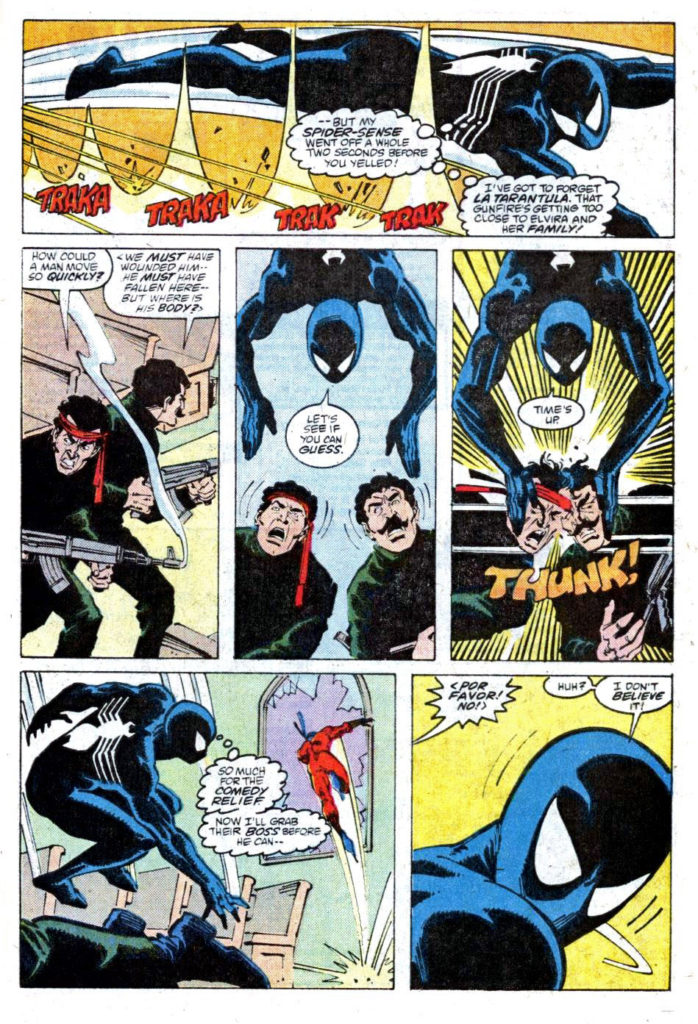

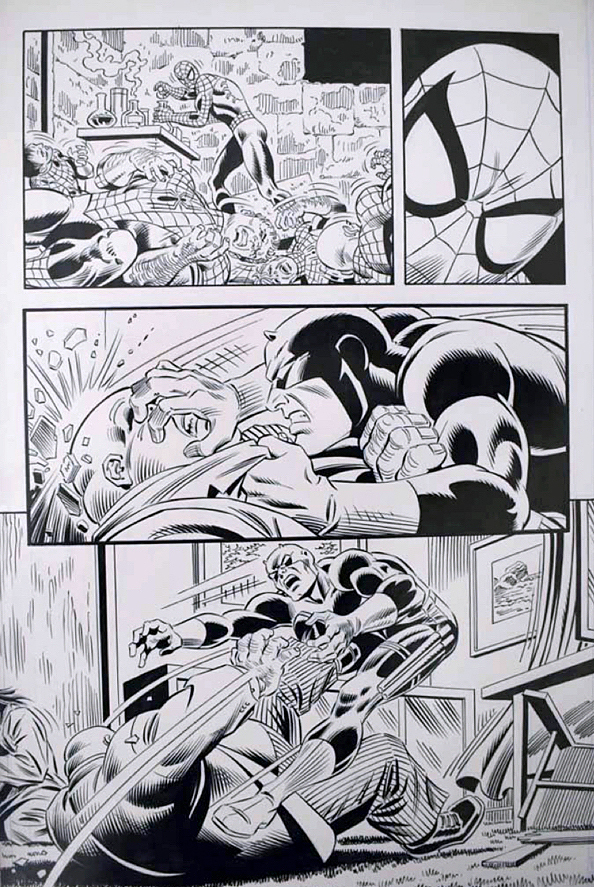

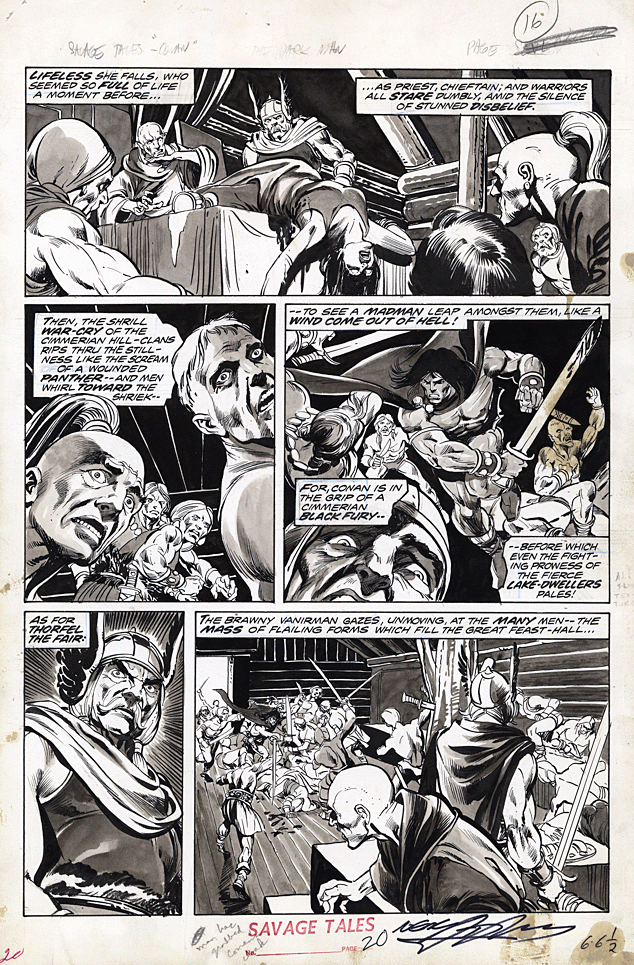

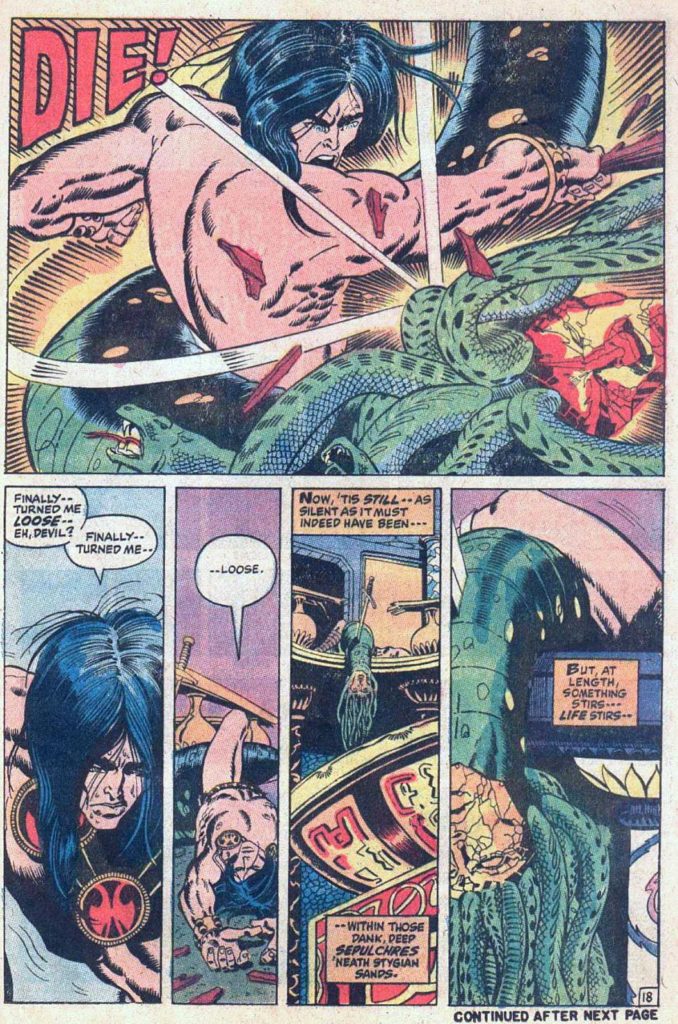

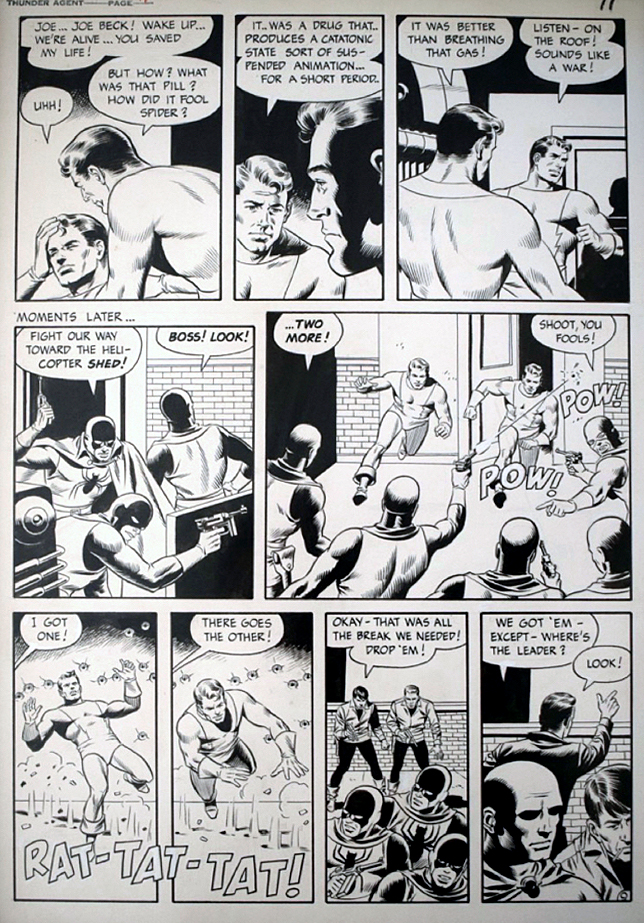

This page is a great example Wood’s crystal clear storytelling and trademark inks. Adkins is credited in some instances on this story as the penciller, with Wood on inks, and due to the collaborative nature of the creative teams on these stories, it’s often easy to lose the thread of who did what.

But this looks like pure Wood here, as Dynamo and his “duplicate” (there are actually three Dynamos in this story — don’t ask) are mowed down in a hail of bullets.

I’ve I always wanted to use that phrase.

Who are you going to call?:

T.H.U.N.D.E.R. The Higher United Nations Defense Enforcement Reserves.

U.N.C.LE. United Network Command for Law and Enforcement.

S.H.I.E.L.D: Originally Supreme Headquarters, International Espionage and Law-Enforcement Division and later Strategic Hazard Intervention Espionage Logistics Directorate. In the MCU film and TV Universe, it means Strategic Homeland Intervention, Enforcement and Logistics Division.